The problem of cabin air contamination in airliners, which can make flight crews seriously ill, has been known for decades. But the airlines are still playing down the health and safety risks.

Last March, in front of Jetblue's head office in New York, dozens of flight attendants chanted: "Fume events are real!” It was an unprecedented demonstration, designed to sound the alarm about the incidents of fumes, known as "fume events", that occur on board aircraft.

They generate unpleasant odors, contaminate the air and, as MEDIAPART has detailed, cause a range of neurological and respiratory symptoms and disabling disorders in aircrew, known as aerotoxic syndrome.

"The American Aviation Federation and aircraft manufacturers are ignoring this health risk, even after reports of crews falling ill", says Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat senator from Connecticut, who also introduced a bill for the third time in March calling for training and protection for passengers.

Fume events are still a little-known phenomenon among the general public, as the aviation industry keeps such incidents under wraps. For almost seventy years, airlines and manufacturers have been trying to downplay the consequences for the health of their crews and flight safety. Firstly, by invoking the "rarity" of these events: one in every two thousand flights, according to the aviation industry. Secondly, by systematically refuting the long-term effects of exposure to contaminated air.

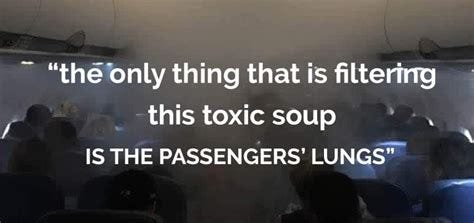

The 'omerta*' reigns over what aircrew refer to as the "shameful little secret" of world aviation. Yet the source of the smoke events is well identified: it is the pressurization and air-conditioning system used on virtually all commercial aircraft. The air circulating on board is drawn in via the jet engine compressors and arrives unfiltered in the cabin. Leaky or worn engine seals inevitably lead to leaks of oil, which, when heated to very high temperatures, releases many toxic substances.

Over the years, and with the number of victims growing, concern has increased among pilots and cabin crew unions around the world. In Australia in 1997, the Senate adopted a report from the occupational health department at Melbourne Airport confirming the existence of a major health problem. In 2009, in France, two Air France CHSCTs (Ed: Health, Safety and Working Conditions Committee) aimed to protect the health and safety of company employees. They demanded an expert report, which confirmed the risk of damage to the health of employees and passengers.

But it was not until 2015 that the scandal broke publicly, with the filing of four complaints by flight crews: Alaska Airlines against Boeing, which resulted in confidential financial agreements. In the aftermath, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) issued a non-binding circular to airlines recommending "staff training in fume events and the systematic reporting of such events". Airbus, for its part, published a report, accompanied by a decontamination-maintenance procedure.

‘Lucien’ (Ed: name changed), 40, a former Air France pilot who lost 48% of his respiratory capacity and was dismissed as not fit to work in 2020, says: “This procedure (Ed: aircraft check and decontamination procedure, see above, after fume event) requires the aircraft to be grounded for two days, which is incompatible with the sector's need for profitability. In reality, it is not applied!”

In 2016 in France, Éric BAILET, then an EasyJet pilot, set up the Association des victimes du syndrome aérotoxique (AVSA). In 2015, on the last of his four flights for the day, he and his co-pilot were taken ill. Medically dismissed in 2018, he lodged a complaint against "X" with the Paris public prosecutor's office for "endangering the lives of others".

Last October, it was the turn of the International Federation of Airline Pilots (IFALPA), which groups 110,000 pilots from nearly one hundred countries, to warn that "exposure to these fumes can cause long-term health effects in addition to occasional problems".

Technical Alternatives ruled out

According to Éric BAILET, despite these warnings, the aviation industry persists in a strategy reminiscent of the "doubt tactics" that were used by the tobacco and pesticide industries to gain time and prevent any public health or environmental regulations. The industry always uses the same language, like Airbus, which claims that the cabin air is "often cleaner than that in other indoor environments such as homes".

Technically, however, there is an alternative to the bleed air system. The Boeing 787 "Dreamliner" that entered service in 2009, uses electric compressors that capture outside air directly, without passing through the engines. But it is still the only one of its kind and accounts for just 0.03% of the world fleet (2020 figures). At the same time, the industry is making discreet moves, as if to anticipate the day when more stringent regulations will be imposed. Patents to reduce engine oil leaks were filed by Airbus in 2017 and Boeing in 2018. But no concrete results have been achieved. Similarly, some airlines have initially opted for engine oils that are considered less dangerous, but only belatedly.

EasyJet, for example, replaced its oil supplier with NYCO in 2017. This French manufacturer had alerted the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in 2019 to the risk of exposure "…of passengers and crew to organophosphates (neurotoxicity), similar to the symptoms of farmers exposed to pesticides..", and developed less toxic oils. The filters and sensors called for by IFALPA and the Global Cabin Air Quality Executive (GCAQE), an international organization set up in 2006 in the United Kingdom to bring together aircrew, engineers, and scientists, remain a “dead” letter.

This doesn't stop airlines from boasting in their brochures about the effectiveness of the filters fitted to the majority of aircraft on commercial flights, which are said to guarantee "air as clean as in an operating theatre".

Unprotected Staff and Passengers

"Yet these filters are ineffective against nanoparticles", says Lucien, the Air France pilot who was dismissed due to (Ed: medical) unfitness. A flight attendant with HOP, Lionel deplores the lack of information among staff: "We have no real awareness of this phenomenon, which is one of the other risk exposure factors (staggered working hours, night work, ionizing radiation, etc.) in our profession".

Since aerotoxic syndrome is not recognized by either the airlines or the health authorities, flight crews have no individual protection. At Air France, the occupational physician coordinating the medical service, Michel Klerlein, assures us that "since all the studies carried out to date on aircraft have not demonstrated the slightest presence of neurotoxic products in the cabin air", there is no need for specific equipment.

There is no systematic medical follow-up after exposure, although this is recommended in numerous official documents. “Pilots are told to wear their oxygen mask if there is the slightest doubt that the aircraft is depressurized," he points out. Commercial pilots have a full-face oxygen mask that can be used for twenty minutes in case of fire/smoke onboard.

Inadequate, say the pilots. “In the event of a smoke event, the procedure requires us to make an emergency landing," explains Éric BAILET. “On a long-haul flight, the oxygen autonomy of the mask is insufficient to do this!”

A 2017 report by the Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses (BEA) on a fume event that left the flight crew partially incapacitated, states that "the implementation of prior local agreements between aircraft operators, airport authorities and emergency medical structures present at airports" would facilitate "the carrying out of medical examinations for aetiological purposes in the immediate aftermath of incidents linked to cabin air quality".

Julie has had a painful experience with this lack of support. Last June, this experienced flight attendant, on a fixed-term contract with Air France, was working on a flight from Paris to Athens when a particularly acute fume event occurred. "When I got home, I felt like I was dying". Fainting, nausea, trembling, exhaustion... She lost 8 kilos in a week.

After a month's sick leave, Air France terminated her contract.

During the fume event, neither Julie nor her colleagues put on an oxygen mask." For fear of creating panic and because protecting themselves would mean acknowledging that there was a problem", she regrets. A law of silence that revolts her: "I think of the two hundred passengers who were on the flight]. Some of them may have been or still are ill. They don't even know why.” (Ed: more testimonies and case studies from aircrew and passengers case studies HERE)

Note:

This article was first published by MEDIAPART on November 19th, 2023 - With thanks for their great work, the articles on the subject are written and researched by Patricia Oudit and Eliane Patriarca - All Rights ©. (Translation, some paraphrasing, highlighted phrases, and added Ed notes by BB). MEDIAPART is published by Société Editrice de Mediapart - 127 Avenue Ledru-Rollin, 75011 Paris. RCS Paris 500 631

This documentary by Tim van Beveren investigates aerotoxic syndrome, including the issues of fume events and tricresyl phosphate (TCP), with input from researchers, and from pilots who claim to be affected by such fumes.

Find all the information you need on these websites UNFILTERED (English and Spanish) and AVSA (French). Please support our PETITION .

To help spread the word, please LIKE, SHARE, and SUBSCRIBE - it’s FREE!

Note: *Omerta: A rule or code that prohibits speaking or divulging information about certain activities, especially the activities of a criminal organization.

--